The three-tier constitution was a delicate mechanism with numerous checks and balances. Without the fullest cooperation between the major parties it was impossible to draft a new constitution, much less to work it. This cooperation was, however, lacking. The Cabinet Mission Plan was a compromise but it did not really bring the two parties together. The result was that questions presumed to have been settled by the Cabinet Mission were reopened soon after the return of its three members to England. Controversy rose to a fever pitch on two crucial issues, that of the "grouping"of provinces and the composition of the "interim government".

Thursday, July 17, 2008

Mahatma Gandhi Life History: Cabinet Mission

Early in 1946, the Labour Government despatched an all-party parliamentary delegation to India

despatched an all-party parliamentary delegation to India to meet Indian leaders and convince them of the British desire for an early settlement of the Indian constitutional issue. However, it was only in March 1946 that with the arrival of three Cabinet Ministers, Lord Pethick-Lawrence, Sir Stafford Cripps and Mr. A. V. Alexander, a crucial stage was reached in the negotiations between the British Government and the Indian political parties. The negotiations were conducted on behalf of the Congress by Abul Kalam Azad

to meet Indian leaders and convince them of the British desire for an early settlement of the Indian constitutional issue. However, it was only in March 1946 that with the arrival of three Cabinet Ministers, Lord Pethick-Lawrence, Sir Stafford Cripps and Mr. A. V. Alexander, a crucial stage was reached in the negotiations between the British Government and the Indian political parties. The negotiations were conducted on behalf of the Congress by Abul Kalam Azad who was assisted by Nehru

who was assisted by Nehru  and Patel. Gandhi

and Patel. Gandhi  was, however, frequently consulted. The negotiations were bogged down on the basic question whether India was to remain united or to be split up to satisfy the Muslim League’s demand for Pakistan. The Congress opposed to the partition of the country, but was prepared to go to the farthest limit in conceding cultural, economic and regional autonomy to various regions. A conference at Simla failed to resolve the Congress-League differences. The Cabinet Mission then offered a compromise plan in their statement of May 16,1946. They sketched a three-tier constitutional structure for India. On the top was to be a Union of India embracing British India as well as the Indian States, but dealing only with foreign affairs, defence and communications. The bottom tier was to consist of Provinces and States in which were to vest all residuary powers. The intermediate tier was to comprise "groups" to be formed by Provinces (if they chose) to deal with certain common subjects. The Muslim League avowed its acceptance of the Cabinet Mission Plan, but this acceptance was more apparent than real, The League and its leaders made no secret of their hope and design that the new constitution would be used to effect a partition of the country. "Let me tell you," Jinnah told the Muslim

was, however, frequently consulted. The negotiations were bogged down on the basic question whether India was to remain united or to be split up to satisfy the Muslim League’s demand for Pakistan. The Congress opposed to the partition of the country, but was prepared to go to the farthest limit in conceding cultural, economic and regional autonomy to various regions. A conference at Simla failed to resolve the Congress-League differences. The Cabinet Mission then offered a compromise plan in their statement of May 16,1946. They sketched a three-tier constitutional structure for India. On the top was to be a Union of India embracing British India as well as the Indian States, but dealing only with foreign affairs, defence and communications. The bottom tier was to consist of Provinces and States in which were to vest all residuary powers. The intermediate tier was to comprise "groups" to be formed by Provinces (if they chose) to deal with certain common subjects. The Muslim League avowed its acceptance of the Cabinet Mission Plan, but this acceptance was more apparent than real, The League and its leaders made no secret of their hope and design that the new constitution would be used to effect a partition of the country. "Let me tell you," Jinnah told the Muslim  League Council on June 5, 1946 "that Muslim India will not rest content until we have established full, complete and sovereign Pakistan." It was this apparent contradiction in the League’s stand, which made Gandhi and his colleagues in the Congress uneasy about the "grouping of provinces", which the League wanted to make compulsory and a stepping-stone to Pakistan. The controversy on this issue wrecked the Cabinet Mission Plan.

League Council on June 5, 1946 "that Muslim India will not rest content until we have established full, complete and sovereign Pakistan." It was this apparent contradiction in the League’s stand, which made Gandhi and his colleagues in the Congress uneasy about the "grouping of provinces", which the League wanted to make compulsory and a stepping-stone to Pakistan. The controversy on this issue wrecked the Cabinet Mission Plan.

The three-tier constitution was a delicate mechanism with numerous checks and balances. Without the fullest cooperation between the major parties it was impossible to draft a new constitution, much less to work it. This cooperation was, however, lacking. The Cabinet Mission Plan was a compromise but it did not really bring the two parties together. The result was that questions presumed to have been settled by the Cabinet Mission were reopened soon after the return of its three members to England. Controversy rose to a fever pitch on two crucial issues, that of the "grouping"of provinces and the composition of the "interim government".

The three-tier constitution was a delicate mechanism with numerous checks and balances. Without the fullest cooperation between the major parties it was impossible to draft a new constitution, much less to work it. This cooperation was, however, lacking. The Cabinet Mission Plan was a compromise but it did not really bring the two parties together. The result was that questions presumed to have been settled by the Cabinet Mission were reopened soon after the return of its three members to England. Controversy rose to a fever pitch on two crucial issues, that of the "grouping"of provinces and the composition of the "interim government".

Saturday, June 28, 2008

Mahatma Gandhi Life History: Communal Conflagration

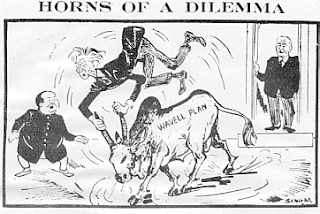

At a time when tension was mounting, it was imperative that the country should have a strong and stable government at the centre. The Cabinet Mission had failed in the formation of a national interim government. In July 1946, the Viceroy, Lord Wavell, once again took the initiative and called upon Jawaharlal Nehru to form the Government. Jinnah, who was approached by Nehru, refused to cooperate, was bitterly critical and announced that August 16 would be observed by the Muslim League as "the Direct Action Day". On that day Calcutta witnessed a communal riot, the scale and intensity of which had never been known in living memory. "The Great Calcutta Killing" touched off a chain reaction of violent communal explosions in East Bengal, Bihar and the Punjab,

As the news of disturbances in Bengal came through, Gandhi cancelled all his plans and decided to leave for the riot-affected areas. In East Bengal he noticed how fear, hatred and violence had come to pervade the countryside. He toured the villages, was things at first hand, and tried to lift the issue of peace from the plane of politics to that of humanity. Whatever the political map of the future, he pleaded, it should be common ground among all parties that standards of civilized life would not be thrown overboard.

Gandhi’s presence acted as a soothing balm on the villages of East Bengal; he eased tensions, assuaged anger and softened. In March 1947, he left for Bihar where the Hindu peasants had wreaked a terrible vengeance on the Muslim minority for the misdeeds of the Muslim majority in East Bengal. In Bihar, Gandhi’s refrain was the same as in East Bengal: the majority community must repent and make amends; the minority must forgive and make a fresh start. He would not accept any apology for what had happened, and chided those who sought in the misdeeds. Of the rioters in East Bengal, a justification for what had happened in Bihar. Civilized conduct, he argued, was the duty of every individual and every community irrespective of what others did

Alarmed by the increasing lawlessness, Lord Wavell brought the Muslim League into the Interim Government. The formation of the coalition between the Congress and the League fanned political controversy instead of putting it out. The Constituent Assembly had been summoned to meet on December 9, 1946, but the Muslim League refused to participate in its deliberations. The constitutional impasse looked complete when in the last week on November in an eleventh hour bid to bring the parties together, the British Government invited Wavell, Nehru, Jinnah, Liaquat Ali and Baldev Singh to London. The discussion proved

Abortive, but the British Government issued a statement to clarify the points at dispute. Though this clarification largely met its objections, the Muslim League did not lift its boycott of the Constituent Assembly.

The year 1947 dawned with the darkest possible prospects on the political horizon. To check the drift to chaos, Clement Attlee, the British Premier, came to the conclusion that what was needed was a new policy and a new Viceroy to carry it out. He announced in the House of Commons on February 20, 1947 that the British Government definitely intended to quit India by June 1948, and if by that date the Indian parties did not agree on an all-India constitution, power would be transferred to "some form of Central Government in British India or in some areas to the existing Provincial Governments." Simultaneously it was announced that Lord Mountbatten would succeed Lord Wavell as Viceroy.

The new Viceroy, with Lord Wavell

The British withdrawal had been decided and dated by the February20th statement. Lord Mountbatten arrived in India in March and one of his first acts as Viceroy was to invite Gandhi for a discussion. The Mahatma interrupted his peace mission in Bihar and travelled to New Delhi. During the next few weeks it became evident that a solution of the political deadlock would be sought through the division of India. The Muslim League led by Jinnah was adamant, but there was also a re-orientation of the Congress attitude towards partition. Hitherto the Congress had insisted that partition should, if at all, follow and not precede political liberation, that there could be "no divorce before marriage". But the few months of stormy courtship in the Interim Government had cured Nehru, Patel and other Congress leaders of the desire for a closer union with the Muslim League. In the spring of 1947, the choice seemed to them to be between anarchy and partition; they resigned themselves to the latter in order to salvage three-fourths of India from the chaos which threatened the whole.

As the news of disturbances in Bengal came through, Gandhi cancelled all his plans and decided to leave for the riot-affected areas. In East Bengal he noticed how fear, hatred and violence had come to pervade the countryside. He toured the villages, was things at first hand, and tried to lift the issue of peace from the plane of politics to that of humanity. Whatever the political map of the future, he pleaded, it should be common ground among all parties that standards of civilized life would not be thrown overboard.

Gandhi’s presence acted as a soothing balm on the villages of East Bengal; he eased tensions, assuaged anger and softened. In March 1947, he left for Bihar where the Hindu peasants had wreaked a terrible vengeance on the Muslim minority for the misdeeds of the Muslim majority in East Bengal. In Bihar, Gandhi’s refrain was the same as in East Bengal: the majority community must repent and make amends; the minority must forgive and make a fresh start. He would not accept any apology for what had happened, and chided those who sought in the misdeeds. Of the rioters in East Bengal, a justification for what had happened in Bihar. Civilized conduct, he argued, was the duty of every individual and every community irrespective of what others did

Alarmed by the increasing lawlessness, Lord Wavell brought the Muslim League into the Interim Government. The formation of the coalition between the Congress and the League fanned political controversy instead of putting it out. The Constituent Assembly had been summoned to meet on December 9, 1946, but the Muslim League refused to participate in its deliberations. The constitutional impasse looked complete when in the last week on November in an eleventh hour bid to bring the parties together, the British Government invited Wavell, Nehru, Jinnah, Liaquat Ali and Baldev Singh to London. The discussion proved

Abortive, but the British Government issued a statement to clarify the points at dispute. Though this clarification largely met its objections, the Muslim League did not lift its boycott of the Constituent Assembly.

The year 1947 dawned with the darkest possible prospects on the political horizon. To check the drift to chaos, Clement Attlee, the British Premier, came to the conclusion that what was needed was a new policy and a new Viceroy to carry it out. He announced in the House of Commons on February 20, 1947 that the British Government definitely intended to quit India by June 1948, and if by that date the Indian parties did not agree on an all-India constitution, power would be transferred to "some form of Central Government in British India or in some areas to the existing Provincial Governments." Simultaneously it was announced that Lord Mountbatten would succeed Lord Wavell as Viceroy.

The new Viceroy, with Lord Wavell

The British withdrawal had been decided and dated by the February20th statement. Lord Mountbatten arrived in India in March and one of his first acts as Viceroy was to invite Gandhi for a discussion. The Mahatma interrupted his peace mission in Bihar and travelled to New Delhi. During the next few weeks it became evident that a solution of the political deadlock would be sought through the division of India. The Muslim League led by Jinnah was adamant, but there was also a re-orientation of the Congress attitude towards partition. Hitherto the Congress had insisted that partition should, if at all, follow and not precede political liberation, that there could be "no divorce before marriage". But the few months of stormy courtship in the Interim Government had cured Nehru, Patel and other Congress leaders of the desire for a closer union with the Muslim League. In the spring of 1947, the choice seemed to them to be between anarchy and partition; they resigned themselves to the latter in order to salvage three-fourths of India from the chaos which threatened the whole.

Sunday, June 22, 2008

Mahatma Gandhi Life History: Partition Of India

As the interminable caravans of refugees with their tales of woes crawled to their destinations, violence spread. When Gandhi arrived in Delhi early in September, he found it paralysed by communal tension. The Government, led by Nehru, had acted energetically and impartially. Gandhi was not content with a peace imposed by the police and the military; he wanted violence to be purged form the hearts of Hindus and Muslims. It was an uphill task. Delhi had a number of refugee camps, some of which housed Hindus and Sikhs from West Pakistan, while others sheltered Muslims fleeing from Delhi for a passage across the border.

Mahatma Gandhi Life History: Mission Of Peace

The tales of woe that Gandhi heard burned themselves into his soul, but he did not falter in his conviction that only non-violence and love could end this spiral of hate and violence. In his prayer speech every evening, he touched on this problem. He stressed the futility of retaliation. He wore himself out in an effort to re-educate the people; he heard grievances, suggested solutions, encouraged or admonished his numerous interviewers, visited refugee camps, remained in touch with local officials.

On January 13, 1948, he began a fast; "my greatest fast," he wrote to Mirabehn, his English disciple. It was also to be his last. The fast was not to be broken until Delhi became peaceful. The fast had a refreshing impact upon Pakistan. In India there was an emotional shake-up. The fast compelled people to think afresh on the problem on the solution of which he had staked his life. On January 18, representatives of various communities and parties in Delhi signed a pledge in Gandhi’s presence that they would guarantee peace in Delhi.

After this fast the tide of violence showed definite signs of ebbing. Gandhi felt free to make his plans for the future. He thought he should visit Pakistan to promote the process of reconciliation between the two countries and the two communities.

Newspaper report on riots in East Bengal

Newspaper report on riots in East Bengal Gandhi in Noakhali

Gandhi in Noakhali January 30, 1948: A page from Jawaharlal Nehru’s diary recording Gandhi’s assassination

January 30, 1948: A page from Jawaharlal Nehru’s diary recording Gandhi’s assassination

Even as he had grappled with communal violence, the real problems of India, the social and economic uplift of her people, had never been absent from his mind. Political freedom having become a fact, Gandhi’s mind was switching more and more to constructive work, and to the refurbishing of his non-violent technique.

On January 13, 1948, he began a fast; "my greatest fast," he wrote to Mirabehn, his English disciple. It was also to be his last. The fast was not to be broken until Delhi became peaceful. The fast had a refreshing impact upon Pakistan. In India there was an emotional shake-up. The fast compelled people to think afresh on the problem on the solution of which he had staked his life. On January 18, representatives of various communities and parties in Delhi signed a pledge in Gandhi’s presence that they would guarantee peace in Delhi.

After this fast the tide of violence showed definite signs of ebbing. Gandhi felt free to make his plans for the future. He thought he should visit Pakistan to promote the process of reconciliation between the two countries and the two communities.

Newspaper report on riots in East Bengal

Newspaper report on riots in East Bengal Gandhi in Noakhali

Gandhi in Noakhali January 30, 1948: A page from Jawaharlal Nehru’s diary recording Gandhi’s assassination

January 30, 1948: A page from Jawaharlal Nehru’s diary recording Gandhi’s assassinationEven as he had grappled with communal violence, the real problems of India, the social and economic uplift of her people, had never been absent from his mind. Political freedom having become a fact, Gandhi’s mind was switching more and more to constructive work, and to the refurbishing of his non-violent technique.

Gandhi And Non-Violence

Gandhi did not claim to be a prophet or even a philosopher. "There is no such thing as Gandhism," he warned, "and I do not want to leave any sect after me." There was only one Gandhian, he said, an imperfect one at that: himself.

The real significance of the Indian freedom movement in Gandhi’s eyes was that it was waged non-violently. He would have had no interest in it if the Indian National Congress had adopted Satyagraha and subscribed to non-violence. He objected to violence not only because an unarmed people had little chance of success in an armed rebellion, but because he considered violence a clumsy weapon which created more problems than it solved, and left a trail of hatred and bitterness in which genuine reconciliation was almost impossible.

This emphasis on non-violence jarred alike on Gandhi’s British and Indian critics, though for different reasons. To the former, non-violence was a camouflage; to the latter, it was sheer sentimentalism. To the British who tended to see the Indian struggle through the prism of European history, the professions of non-violence rather than on the remarkably peaceful nature of Gandhi’s campaigns. To the radical Indian politicians, who had browsed on the history of the French and Russian revolutions or the Italian and Irish nationalist struggles, it was patent that force would only yield to force, and that it was foolish to miss opportunities and sacrifice tactical gains for reasons more relevant to ethics than to politics.

Gandhi’s total allegiance to non-violence created a gulf between him and the educated elite in India which was temporarily bridged only during periods of intense political excitement. Even among his closest colleagues there were few who were prepared to follow his doctrine of non-violence to its logical conclusion: the adoption of unilateral disarmament in a world armed to the teeth, the scrapping of the police and the armed forces, and the decentralization of administration to the point where the state would "wither away". Nehru, Patel and others on whom fell the task of organizing the administration of independent India did not question the superiority of the principle of non-violence as enunciated by their leader, but they did not coperider it practical politics. The Indian Constituent Assembly include a majority of members owing allegiance to Gandhi or at least holding him in high esteem, but the constitution which emerged from their labours in 1949 was based more on the Western parliamentary than on he Gandhian model. The development of the Indian economy during the last four decades cannot be said to have conformed to Gandhi’s conception of "self-reliant village republics". On the other hand, it bears the marks of a conscious effort to launch an Indian industrial revolution.

Jawaharlal Nehru—Gandhi’s "political heir"—was thoroughly imbued with the humane values inculcated by the Mahatma. But the man who spoke Gandhi’s language, after his death, was Vinoba Bhave, the "Walking Saint", who kept out of politics and government, Bhave’s Bhoodan (land gift) Movement was designed as much as a measure of land reform as that of a spiritual renewal. Though more than five million acres of land were distributed to the landless, the movement, despite its early promise, never really spiralled into a social revolution by consent. This was partly because Vinoba Bhave did not command Gandhi’s extraordinary genius for organizing the masses for a national crusade, and partly because in independent India the tendency grew for the people to look up to the government rather than to rely on voluntary and cooperative effort for effecting reforms in society.

Soon after Gandhi’s death in 1948, a delegate speaking at the United Nations predicted that "the greatest achievements of the Indian sage were yet to come" "Gandhi’s times," said Vindba Bhave, "were the first pale dawn of the sun of Satyagraha." Forty years after Gandhi’s death, this optimism would seem to have been too high-pitched. The manner in which Gandhi’s techniques have sometimes been invoked even in the land of his birth in recent years would appear to be a travesty of his principles. And the world has been in the grip of a series of crises in Korea, the Congo, the Vietnam, the Middle East, and South Africa with a never-ending trail of blood and bitterness. The shadow of a thermo-nuclear war with its incalculable hazards continues to hang over mankind. From this predicament, Gandhi’s ideas and techniques may suggest a way out. Unfortunately, his motives and methods are often misunderstood, and not only by mobs in the street, Not long ago, Arthur Koestler described Gandhi’s attitude as one "of passive submission to bayonetting and raping, to villages without sewage, septic childhood's and trachoma." Such a judgement is of course completely with the same tenacity with which he battled with the British Raj. He advocated non-violence not because it offered an easy way out, but because he considered violence a crude and in the long run, an ineffective weapon. His rejection of violence stemmed from choice, not from necessity.

Horace Alexander, who knew Gandhi and saw him in action, graphically describes the attitude of the non-violent resister to his opponent: "On your side you have all the mighty forces of the modern State, arms, money, a controlled press, and all the rest. On my side, I have nothing but my conviction of right and truth, the unquenchable spirit of man, who is prepared to die for his convictions than submit to your brute force. I have my comrades in armlessness. Here we stand; and here if need be, we fall." Far from being a craven retreat from difficulty and danger, non-violent resistance demands courage of a high order, the courage to resist injustice without rancour, to unite the utmost firmness with the utmost gentleness, to invite suffering but not to inflict it, to die but not to kill.

Gandhi did not make the facile division of mankind into "good" and "bad" He was convinced that every human being—even the "enemy" –had a kernel of decency: there were only evil acts, no wholly evil men. His technique of Satyagraha was designed not to coerce the opponent, but to set into motion forces which could lead to his conversion. Relying as it did on persuasion and compromise, Gandhi’s method was not always quick in producing results, but the results were likely to be the more durable for having been brought about peacefully. "It is my firm conviction," Gandhi affirmed, "that nothing enduring can be built upon violence. " The rate of social change through the non-violent technique was not in fact likely to be much slower than that achieved by violent methods; it was definitely faster than that expected from the normal functioning of institutions which tended to fossilize and preserve the status quo.

Gandhi did not think it possible to bring about radical changes in the structure of society overnight. Nor did he succumb to the illusion that the road to a new order could be paved merely with pious wishes and fine words. It was not enough to blame the opponent or bewail the times in which one’s lot was cast. However heavy the odds, it was the Satyagrahi’s duty never to feel helpless. The least he could do was to make a beginning with himself. If he was crusading for a new deal for peasantry, he could go to a village and live there, If he wanted to bring peace to a disturbed district, he could walk through it, entering into the minds and hearts of those who were going through the ordeal, If an age-old evil like untouchability was to be fought, what could be a more effective symbol of defiance for a reformer than to adopt an untouchable child? If the object was to challenge foreign rule, why not act on the assumption that the country was already free, ignore the alien government and build alternative institutions to harness the spontaneous, constructive and cooperative effort of the people? If the goal was world peace, why not begin today by acting peacefully6n towards the immediate neighbour, going more than half way to understand and win him over?

Though he may have appeared a starry-eyed idealist to so me, Gandhi’s attitude to social and political problems was severely practical. There was a deep mystical streak in him, but even his mysticism seemed to have little of the ethereal about it. He did not dream heavenly dreams nor see things unutterable in trance; when "the still small voice" spoke to him, it was often to tell how he could fight a social evil or heal a rift between two warring communities. Far from distracting him from his role in public affairs, Gandhi’s religious quest gave him the stamina to play it more effectively. To him true religion was not merely the reading of scriptures, the dissection of ancient texts, or even the practice of cloistered virtue: it had to be lived in the challenging context of political and social life.

Gandhi used his non-violent technique on behalf of his fellow-countrymen in South Africa and India, but he did not conceive it only as a weapon in the armoury of Indian nationalism. On the other hand, he fashioned it as an instrument for righting wrongs and resolving conflicts between opposing groups, races and nations. It is a strange paradox that though the stoutest and perhaps the most successful champion of the revolt against colonialism in our time, Gandhi was frees from the taint of narrow nationalism. As early as 1924, he had declared that "the better mind of the world desires today, not absolutely independent states, warring one against another, but a federation of independent, of friendly interdependent states"

Even before the First World War had revealed the disastrous results of the combination of industrialism and nationalism, he had become a convert to the idea that violence between nation-states must be completely abjured.

In 1931,during his visit to England, a cartoon in the Star depicted him in a loin cloth besides Mussolini, Hitler, de Valera and Stalin, who were clad in black, brown, green and red shirts respectively. The caption, "And he ain’t wearing any blooming’ shirt at all" was not only literally but figuratively true. For a man of non-violence, who believed in the brotherhood of man, there was no superficial division of nations into good and bad, allies and adversaries. This did not, however, mean that Gandhi did not distinguish between the countries which inflicted and the countries which suffered violence. His own life had been one struggle against the forces of violence, and Satyagraha was designed at once to eschew violence and to fight injustice.

In the years immediately preceding the Second Word war, when the tide of Nazi and Fascist aggression was relentlessly rolling forward, Gandhi had reasserted his faith in non-violence and commended it to the smaller nation which were living in daily dread of being overwhelmed by superior force. Through the pages of his weekly paper the Harijan, he expounded the non-violent approach to military aggression and political tyranny. He advised the weaker nations to defend themselves not by increasing their fighting potential, but by non-violent resistance to the aggressor. When Czechoslovakia was black-mailed into submission in September 1938, Gandhi suggested to the unfortunate Czechs: "There is no bravery greater than a resolute refusal

To bend the knee to an earthly power, no matter how great, and that without bitterness of spirit, and in the fulness of faith that the spirit alone lives, nothing else does."

Seven years later when the first atomic bombs exploded over Hiroshima and Nagasaki, Gandhi’s reaction was characteristic: "I did not move a muscle. On the contrary, I said to myself that unless now the adopts non-violence, it will spell certain suicide for mankind." The irony of the very perfection of the weapons of war rendering them useless as arbiters between nations has become increasingly clear during the last forty years. The atomic stockpiles which the major nuclear powers have already built up are capable of destroying civilization, as we know it several time over and peace has been precariously preserved by, what has been grimly termed, "the balance of atomic terror." The fact is that with the weapons of mass destruction, which are at hand now, to attack another nation is tantamount to attacking oneself. This is a bitter truth which old habits of thought have prevented from going home. "This splitting of the atoms has changed everything"bewailed Einstein, "save our modes of thinking and thus we drift towards unparallelled catastrophe."

Non-violence, as Gandhi expounded it, has ceased to be a pious exhortation, and become a necessity. The advice he gave to the unfortunate Abyssinians and Czechs during the twilight years before the Second Word War, may have seemed utopian thirty years ago. Today, it sounds commonsense. Even some hardheaded military strategists such as Sir Stephen King-Hall have begun to see in Gandhi’s method a possible alternative to suicidal violence.

Gandhi would have been the first to deny that his method offered an instant or universal panacea for world peace. His method is capable of almost infinite evolution to suit new situations in a changing world. It is possible that "applied nonviolence" is at present at the same

Stage of development "as the invention of electricity was in the days of Edison and Marconi." The lives-and deaths-of Chief Lithuli and Dr. Martin Luther King have proved that there is nothing esoteric about non-violence, limiting it to a particular country or a particular period. Indeed Tagore, the great contemporary and friend of Gandhi, prophesies that the West would accept Gandhi before the East "for the West has gone through the cycle of dependence on force and material things of life and has become disillusioned. They want a return to the spirit. The East has not yet gone through materialism and hence has not become so disillusioned."

The real significance of the Indian freedom movement in Gandhi’s eyes was that it was waged non-violently. He would have had no interest in it if the Indian National Congress had adopted Satyagraha and subscribed to non-violence. He objected to violence not only because an unarmed people had little chance of success in an armed rebellion, but because he considered violence a clumsy weapon which created more problems than it solved, and left a trail of hatred and bitterness in which genuine reconciliation was almost impossible.

This emphasis on non-violence jarred alike on Gandhi’s British and Indian critics, though for different reasons. To the former, non-violence was a camouflage; to the latter, it was sheer sentimentalism. To the British who tended to see the Indian struggle through the prism of European history, the professions of non-violence rather than on the remarkably peaceful nature of Gandhi’s campaigns. To the radical Indian politicians, who had browsed on the history of the French and Russian revolutions or the Italian and Irish nationalist struggles, it was patent that force would only yield to force, and that it was foolish to miss opportunities and sacrifice tactical gains for reasons more relevant to ethics than to politics.

Gandhi’s total allegiance to non-violence created a gulf between him and the educated elite in India which was temporarily bridged only during periods of intense political excitement. Even among his closest colleagues there were few who were prepared to follow his doctrine of non-violence to its logical conclusion: the adoption of unilateral disarmament in a world armed to the teeth, the scrapping of the police and the armed forces, and the decentralization of administration to the point where the state would "wither away". Nehru, Patel and others on whom fell the task of organizing the administration of independent India did not question the superiority of the principle of non-violence as enunciated by their leader, but they did not coperider it practical politics. The Indian Constituent Assembly include a majority of members owing allegiance to Gandhi or at least holding him in high esteem, but the constitution which emerged from their labours in 1949 was based more on the Western parliamentary than on he Gandhian model. The development of the Indian economy during the last four decades cannot be said to have conformed to Gandhi’s conception of "self-reliant village republics". On the other hand, it bears the marks of a conscious effort to launch an Indian industrial revolution.

Jawaharlal Nehru—Gandhi’s "political heir"—was thoroughly imbued with the humane values inculcated by the Mahatma. But the man who spoke Gandhi’s language, after his death, was Vinoba Bhave, the "Walking Saint", who kept out of politics and government, Bhave’s Bhoodan (land gift) Movement was designed as much as a measure of land reform as that of a spiritual renewal. Though more than five million acres of land were distributed to the landless, the movement, despite its early promise, never really spiralled into a social revolution by consent. This was partly because Vinoba Bhave did not command Gandhi’s extraordinary genius for organizing the masses for a national crusade, and partly because in independent India the tendency grew for the people to look up to the government rather than to rely on voluntary and cooperative effort for effecting reforms in society.

Soon after Gandhi’s death in 1948, a delegate speaking at the United Nations predicted that "the greatest achievements of the Indian sage were yet to come" "Gandhi’s times," said Vindba Bhave, "were the first pale dawn of the sun of Satyagraha." Forty years after Gandhi’s death, this optimism would seem to have been too high-pitched. The manner in which Gandhi’s techniques have sometimes been invoked even in the land of his birth in recent years would appear to be a travesty of his principles. And the world has been in the grip of a series of crises in Korea, the Congo, the Vietnam, the Middle East, and South Africa with a never-ending trail of blood and bitterness. The shadow of a thermo-nuclear war with its incalculable hazards continues to hang over mankind. From this predicament, Gandhi’s ideas and techniques may suggest a way out. Unfortunately, his motives and methods are often misunderstood, and not only by mobs in the street, Not long ago, Arthur Koestler described Gandhi’s attitude as one "of passive submission to bayonetting and raping, to villages without sewage, septic childhood's and trachoma." Such a judgement is of course completely with the same tenacity with which he battled with the British Raj. He advocated non-violence not because it offered an easy way out, but because he considered violence a crude and in the long run, an ineffective weapon. His rejection of violence stemmed from choice, not from necessity.

Horace Alexander, who knew Gandhi and saw him in action, graphically describes the attitude of the non-violent resister to his opponent: "On your side you have all the mighty forces of the modern State, arms, money, a controlled press, and all the rest. On my side, I have nothing but my conviction of right and truth, the unquenchable spirit of man, who is prepared to die for his convictions than submit to your brute force. I have my comrades in armlessness. Here we stand; and here if need be, we fall." Far from being a craven retreat from difficulty and danger, non-violent resistance demands courage of a high order, the courage to resist injustice without rancour, to unite the utmost firmness with the utmost gentleness, to invite suffering but not to inflict it, to die but not to kill.

Gandhi did not make the facile division of mankind into "good" and "bad" He was convinced that every human being—even the "enemy" –had a kernel of decency: there were only evil acts, no wholly evil men. His technique of Satyagraha was designed not to coerce the opponent, but to set into motion forces which could lead to his conversion. Relying as it did on persuasion and compromise, Gandhi’s method was not always quick in producing results, but the results were likely to be the more durable for having been brought about peacefully. "It is my firm conviction," Gandhi affirmed, "that nothing enduring can be built upon violence. " The rate of social change through the non-violent technique was not in fact likely to be much slower than that achieved by violent methods; it was definitely faster than that expected from the normal functioning of institutions which tended to fossilize and preserve the status quo.

Gandhi did not think it possible to bring about radical changes in the structure of society overnight. Nor did he succumb to the illusion that the road to a new order could be paved merely with pious wishes and fine words. It was not enough to blame the opponent or bewail the times in which one’s lot was cast. However heavy the odds, it was the Satyagrahi’s duty never to feel helpless. The least he could do was to make a beginning with himself. If he was crusading for a new deal for peasantry, he could go to a village and live there, If he wanted to bring peace to a disturbed district, he could walk through it, entering into the minds and hearts of those who were going through the ordeal, If an age-old evil like untouchability was to be fought, what could be a more effective symbol of defiance for a reformer than to adopt an untouchable child? If the object was to challenge foreign rule, why not act on the assumption that the country was already free, ignore the alien government and build alternative institutions to harness the spontaneous, constructive and cooperative effort of the people? If the goal was world peace, why not begin today by acting peacefully6n towards the immediate neighbour, going more than half way to understand and win him over?

Though he may have appeared a starry-eyed idealist to so me, Gandhi’s attitude to social and political problems was severely practical. There was a deep mystical streak in him, but even his mysticism seemed to have little of the ethereal about it. He did not dream heavenly dreams nor see things unutterable in trance; when "the still small voice" spoke to him, it was often to tell how he could fight a social evil or heal a rift between two warring communities. Far from distracting him from his role in public affairs, Gandhi’s religious quest gave him the stamina to play it more effectively. To him true religion was not merely the reading of scriptures, the dissection of ancient texts, or even the practice of cloistered virtue: it had to be lived in the challenging context of political and social life.

Gandhi used his non-violent technique on behalf of his fellow-countrymen in South Africa and India, but he did not conceive it only as a weapon in the armoury of Indian nationalism. On the other hand, he fashioned it as an instrument for righting wrongs and resolving conflicts between opposing groups, races and nations. It is a strange paradox that though the stoutest and perhaps the most successful champion of the revolt against colonialism in our time, Gandhi was frees from the taint of narrow nationalism. As early as 1924, he had declared that "the better mind of the world desires today, not absolutely independent states, warring one against another, but a federation of independent, of friendly interdependent states"

Even before the First World War had revealed the disastrous results of the combination of industrialism and nationalism, he had become a convert to the idea that violence between nation-states must be completely abjured.

In 1931,during his visit to England, a cartoon in the Star depicted him in a loin cloth besides Mussolini, Hitler, de Valera and Stalin, who were clad in black, brown, green and red shirts respectively. The caption, "And he ain’t wearing any blooming’ shirt at all" was not only literally but figuratively true. For a man of non-violence, who believed in the brotherhood of man, there was no superficial division of nations into good and bad, allies and adversaries. This did not, however, mean that Gandhi did not distinguish between the countries which inflicted and the countries which suffered violence. His own life had been one struggle against the forces of violence, and Satyagraha was designed at once to eschew violence and to fight injustice.

In the years immediately preceding the Second Word war, when the tide of Nazi and Fascist aggression was relentlessly rolling forward, Gandhi had reasserted his faith in non-violence and commended it to the smaller nation which were living in daily dread of being overwhelmed by superior force. Through the pages of his weekly paper the Harijan, he expounded the non-violent approach to military aggression and political tyranny. He advised the weaker nations to defend themselves not by increasing their fighting potential, but by non-violent resistance to the aggressor. When Czechoslovakia was black-mailed into submission in September 1938, Gandhi suggested to the unfortunate Czechs: "There is no bravery greater than a resolute refusal

To bend the knee to an earthly power, no matter how great, and that without bitterness of spirit, and in the fulness of faith that the spirit alone lives, nothing else does."

Seven years later when the first atomic bombs exploded over Hiroshima and Nagasaki, Gandhi’s reaction was characteristic: "I did not move a muscle. On the contrary, I said to myself that unless now the adopts non-violence, it will spell certain suicide for mankind." The irony of the very perfection of the weapons of war rendering them useless as arbiters between nations has become increasingly clear during the last forty years. The atomic stockpiles which the major nuclear powers have already built up are capable of destroying civilization, as we know it several time over and peace has been precariously preserved by, what has been grimly termed, "the balance of atomic terror." The fact is that with the weapons of mass destruction, which are at hand now, to attack another nation is tantamount to attacking oneself. This is a bitter truth which old habits of thought have prevented from going home. "This splitting of the atoms has changed everything"bewailed Einstein, "save our modes of thinking and thus we drift towards unparallelled catastrophe."

Non-violence, as Gandhi expounded it, has ceased to be a pious exhortation, and become a necessity. The advice he gave to the unfortunate Abyssinians and Czechs during the twilight years before the Second Word War, may have seemed utopian thirty years ago. Today, it sounds commonsense. Even some hardheaded military strategists such as Sir Stephen King-Hall have begun to see in Gandhi’s method a possible alternative to suicidal violence.

Gandhi would have been the first to deny that his method offered an instant or universal panacea for world peace. His method is capable of almost infinite evolution to suit new situations in a changing world. It is possible that "applied nonviolence" is at present at the same

Stage of development "as the invention of electricity was in the days of Edison and Marconi." The lives-and deaths-of Chief Lithuli and Dr. Martin Luther King have proved that there is nothing esoteric about non-violence, limiting it to a particular country or a particular period. Indeed Tagore, the great contemporary and friend of Gandhi, prophesies that the West would accept Gandhi before the East "for the West has gone through the cycle of dependence on force and material things of life and has become disillusioned. They want a return to the spirit. The East has not yet gone through materialism and hence has not become so disillusioned."

Mahatma Gandhi Life History: Sevagram Ashram

Sevagram ashram near Wardha in Maharashtra founded by Gandhiji in 1936.

Sevagram ashram near Wardha in Maharashtra founded by Gandhiji in 1936. In January 1948, before three pistol shots put an end to his life, Gandhi had been on the political stage for more than fifty years. He head inspired two generations of India patriots, shaken an empire and sparked off a revolution which was to change the face of Africa and Asia. To millions of his own people, he was the Mahatma- the great soul- whose sacred glimpse was a reward in itself. By the end of 1947 he had lived down much of the suspicion, ridicule and opposition which he to face, when he first raised the banner of revolt against racial exclusiveness and imperial domination. His ideas, once dismissed as quaint and utopian ,had begun to strike answering chords in some of the finest minds in the world. "Generations to come, it may be", Einstein had said of Gandhi in July 1944, "will scarcely believe that such a one as this ever in flesh and blood walked upon earth."

Though his life had been continual unfolding of an endless drama, Gandhi himself seemed the least dramatic of men. It would be difficult to imagine a man with fewer trappings of political eminence or with less of the popular image of a heroic figure. With his loin cloth, steel-rimmed glasses, rough sandals, a toothless smile and a voice which rarely rose above a whisper, he had a disarming humility. He used a stone instead of soap for his bath, wrote his letters on little bits of paper with little stumps of pencils which he could hardly hold between his fingers, shaved with a crude country razor and ate with a wooden spoon from a prisoner’s bowl. He was, if one majwere to use the famous words of the Buddha, a man who had "by rousing himself, by earnestness, by restraint and control, made for himself an island which on flood could overwhelm."

Gandhi’s, deepest strivings were spiritual, but he did not-as had been the custom in his country- retire to a cave in the Himalayas to seek his salvation. He carried his cave within him. He did not know, he said, any religion apart from human activity; the spiritual law did not work in a vacuum, but expressed itself through the ordinary activities of life. This aspiration to relate the spirit- not the forms-of religion to the problems of everyday life runs like a thread through Gandhi’s career; his uneventful childhood, the slow unfolding and the near- failure of his youth, reluctant plunge into the politics of Natal, the long, unequal struggle in South Africa, and the vicissitudes of the Indian struggle for freedom, which under his leadership was to culminate in a triumph not untinged with tragedy.

Mahatma Gandhi Life History: The End

However, he was not destined to pick up the threads of his constructive programme. He had a narrow escape on January 20, 1948, when a bomb exploded in Birla House in New Delhi where he was addressing his prayer meeting. He took no notice of the explosion. Next day he referred to the congratulations which he had received for remaining unruffled after the explosion. He would deserve them, he said, if he fell as a result of such an explosion and yet retained a smile on his face and no malice against the assailant. He described the bomb-thrower as a misguided youth and advised the police not to "molest" him but to convert him with persuasion and affection. "The misguided youth" was Madan Lal, a refugee from West Punjab, who was a member of a gang which had plotted Gandhi’s death. These highly-strung youngmen saw Hinduism menaced by Islam from without and by Gandhi from within. Madan Lal having missed his aim, a fellow conspirator from Poona, Nathu Ram Godse, came to Gandhi’s prayer meeting on the evening of January 30, whipped out his pistol and fired three shots. Gandhi fell instantly with the words ‘He Rama’ (Oh! God).

Wednesday, June 18, 2008

Adolf Hitler is Born - April 20, 1889

At 6:30 p.m. on the evening of April 20, 1889, he was born in the small Austrian village of Braunau Am Inn just across the border from German Bavaria.

Adolf Hitler would one day lead a movement that placed supreme importance on a person's family tree even making it a matter of life and death. However, his own family tree was quite mixed up and would be a lifelong source of embarrassment and concern to him.

His father, Alois, was born in 1837. He was the illegitimate son of Maria Anna Schicklgruber and her unknown mate, which may have been someone from the neighborhood or a poor millworker named Johann Georg Hiedler. It is also remotely possible Adolf Hitler's grandfather was Jewish.

Maria Schicklgruber was said to have been employed as a cook in the household of a wealthy Jewish family named Frankenberger. There is some speculation their 19-year-old son got her pregnant and regularly sent her money after the birth of Alois.

Adolf Hitler would never know for sure just who his grandfather was.

He did know that when his father Alois was about five years old, Maria Schicklgruber married Johann Georg Hiedler. The marriage lasted five years until her death of natural causes, at which time Alois went to live on a small farm with his uncle.

At age thirteen, young Alois had enough of farm life and set out for the city of Vienna to make something of himself. He worked as a shoemaker's apprentice then later enlisted in the Austrian civil service, becoming a junior customs official. He worked hard as a civil servant and eventually became a supervisor. By 1875 he achieved the rank of Senior Assistant Inspector, a big accomplishment for the former poor farm boy with little formal education.

At this time an event occurred that would have big implications for the future.

Alois had always used the last name of his mother, Schicklgruber, and thus was always called Alois Schicklgruber. He made no attempt to hide the fact that he was illegitimate since it was common in rural Austria.

But after his success in the civil service, his proud uncle from the small farm convinced him to change his last name to match his own, Hiedler, and continue the family name. However, when it came time to write the name down in the record book it was spelled as Hitler.

And so in 1876 at age 39, Alois Schicklgruber became Alois Hitler. This is important because it is hard to imagine tens of thousands of Germans shouting "Heil Schicklgruber!" instead of "Heil Hitler!"

In 1885, after numerous affairs and two other marriages ended, the widowed Alois Hitler, 48, married the pregnant Klara Pölzl, 24, the granddaughter of uncle Hiedler. Technically, because of the name change, she was his own niece and so he had to get special permission from the Catholic Church.

The children from his previous marriage, Alois Hitler, Jr., and Angela, attended the wedding and lived with them afterwards. Klara Pölzl eventually gave birth to two boys and a girl, all of whom died. On April 20, 1889, her fourth child, Adolf, was born healthy and was baptized a Roman Catholic. Hitler's father was now 52 years old.

Throughout his early days, young Adolf's mother feared losing him as well and lavished much care and affection on him. His father was busy working most of the time and also spent a lot of time on his main hobby, keeping bees.

Baby Adolf had the nickname, Adi. When he was almost five, in 1893, his mother gave birth to a brother, Edmund. In 1896 came a sister, Paula.

In May of 1895 at age six, young Adolf Hitler entered first grade in the public school in the village of Fischlham near Linz, Austria.

Adolf Hitler would one day lead a movement that placed supreme importance on a person's family tree even making it a matter of life and death. However, his own family tree was quite mixed up and would be a lifelong source of embarrassment and concern to him.

His father, Alois, was born in 1837. He was the illegitimate son of Maria Anna Schicklgruber and her unknown mate, which may have been someone from the neighborhood or a poor millworker named Johann Georg Hiedler. It is also remotely possible Adolf Hitler's grandfather was Jewish.

Maria Schicklgruber was said to have been employed as a cook in the household of a wealthy Jewish family named Frankenberger. There is some speculation their 19-year-old son got her pregnant and regularly sent her money after the birth of Alois.

Adolf Hitler would never know for sure just who his grandfather was.

He did know that when his father Alois was about five years old, Maria Schicklgruber married Johann Georg Hiedler. The marriage lasted five years until her death of natural causes, at which time Alois went to live on a small farm with his uncle.

At age thirteen, young Alois had enough of farm life and set out for the city of Vienna to make something of himself. He worked as a shoemaker's apprentice then later enlisted in the Austrian civil service, becoming a junior customs official. He worked hard as a civil servant and eventually became a supervisor. By 1875 he achieved the rank of Senior Assistant Inspector, a big accomplishment for the former poor farm boy with little formal education.

At this time an event occurred that would have big implications for the future.

Alois had always used the last name of his mother, Schicklgruber, and thus was always called Alois Schicklgruber. He made no attempt to hide the fact that he was illegitimate since it was common in rural Austria.

But after his success in the civil service, his proud uncle from the small farm convinced him to change his last name to match his own, Hiedler, and continue the family name. However, when it came time to write the name down in the record book it was spelled as Hitler.

And so in 1876 at age 39, Alois Schicklgruber became Alois Hitler. This is important because it is hard to imagine tens of thousands of Germans shouting "Heil Schicklgruber!" instead of "Heil Hitler!"

In 1885, after numerous affairs and two other marriages ended, the widowed Alois Hitler, 48, married the pregnant Klara Pölzl, 24, the granddaughter of uncle Hiedler. Technically, because of the name change, she was his own niece and so he had to get special permission from the Catholic Church.

The children from his previous marriage, Alois Hitler, Jr., and Angela, attended the wedding and lived with them afterwards. Klara Pölzl eventually gave birth to two boys and a girl, all of whom died. On April 20, 1889, her fourth child, Adolf, was born healthy and was baptized a Roman Catholic. Hitler's father was now 52 years old.

Throughout his early days, young Adolf's mother feared losing him as well and lavished much care and affection on him. His father was busy working most of the time and also spent a lot of time on his main hobby, keeping bees.

Baby Adolf had the nickname, Adi. When he was almost five, in 1893, his mother gave birth to a brother, Edmund. In 1896 came a sister, Paula.

In May of 1895 at age six, young Adolf Hitler entered first grade in the public school in the village of Fischlham near Linz, Austria.

Hitler's Boyhood - 1895-1903

In 1895, at age six, two important events happened in the life of young Adolf Hitler. First, the unrestrained, carefree days he had enjoyed up to now came to an end as he entered primary school. Secondly, his father retired on a pension from the Austrian civil service.

This meant a double dose of supervision, discipline and regimentation under the watchful eyes of teachers at school and his strict father at home. His father, now 58, had spent most of his life working his way up through the civil service ranks. He was used to giving orders and having them obeyed and also expected this from his children. The Hitler family lived on a small farm outside of Linz, Austria. The children had farm chores to perform along with their school work.

Hitler's mother was now preoccupied with caring for her new son, Edmund. In 1896, she gave birth to a girl, Paula. The Hitler household now consisted of Adolf, little brother Edmund, little sister Paula, older half-brother Alois Jr., older half-sister Angela and two parents who were home all the time. It was a crowded, noisy little farm house that seems to have gotten on the nerves on Hitler's father who found retirement after 40 years of work to be difficult.

Hitler's mother was now preoccupied with caring for her new son, Edmund. In 1896, she gave birth to a girl, Paula. The Hitler household now consisted of Adolf, little brother Edmund, little sister Paula, older half-brother Alois Jr., older half-sister Angela and two parents who were home all the time. It was a crowded, noisy little farm house that seems to have gotten on the nerves on Hitler's father who found retirement after 40 years of work to be difficult.

The oldest boy, Alois Jr., 13, bore the brunt of his father's discontent, including harsh words and occasional beatings. A year later, at age 14, young Alois had enough of this treatment and ran away from home, never to see his father again. This put young Adolf, age 7, next in line for the same treatment.

Also at this time, the family moved off the farm to the town of Lambach, Austria, halfway between Linz and Salzburg. This was the first of several moves the family would make during the restless retirement of Hitler's father.

For young Adolf, the move to Lambach meant an end to farm chores and more time to play. There was an old Catholic Benedictine monastery in the town. The ancient monastery was decorated with carved stones and woodwork that included several swastikas. Adolf attended school there and saw them every day. They had been put there in the 1800s by the ruling Abbot as a pun or play on words. His name essentially sounded like the German word for swastika, Hakenkreuz.

Young Hitler did well in the monastery school and also took part in the boys' choir. He was said to have had a fine singing voice. Years later Hitler would say the solemn pageantry of the high mass and other Catholic ceremonies was quite intoxicating and left a very deep impression.

As a young boy he idolized the priests and for two years seriously considered becoming a priest himself. He especially admired the Abbot in charge, who ruled his black-robbed monks with supreme authority. At home Hitler sometimes played priest and even included long sermons.

At age nine, he got into schoolboy mischief. He was caught smoking a cigarette by one of the priests, but was forgiven and not punished.

His favorite game to play outside was cowboys and Indians. Tales of the American West were very popular among boys in Austria and Germany. Books by James Fenimore Cooper and especially German writer Karl May were eagerly read and re-enacted.

May, who had never been to America, invented a hero named Old Shatterhand, a white man who always won his battles with Native Americans, defeating his enemies through sheer will power and bravery. Young Hitler read and re-read every one of May's books about Old Shatterhand, totaling more than 70 novels. He continued to read them even as Führer. During the German attack on the Soviet Union he sometimes referred to the Russians as Redskins and ordered his officers to carry May's books about fighting Indians.

In describing his boyhood, Hitler later said of himself that he was an argumentative little ring leader who liked to stay outside and hang around with 'husky' boys. His half-brother Alois later described him as quick to anger and spoiled by his indulgent mother.

In 1898, the Hitler family moved once again, to the village of Leonding, close to Linz. They settled into a small house with a garden located next to a cemetery. This meant another change of schools for Adolf.

He found school easy and got good grades with little effort. He also discovered he had considerable talent for drawing, especially sketching buildings. He had the ability to look at a building, memorize the architectural details, and accurately reproduce it on paper, entirely from memory.

One day, young Hitler went rummaging through his father's book collection and came across several of a military nature, including a picture book on the War of 1870-71 between the Germans and the French. By Hitler's own account, this book became an obsession. He read it over and over, becoming convinced it had been a glorious event.

"It was not long before the great historic struggle had become my greatest spiritual experience. From then on, I became more and more enthusiastic about everything that was in any was connected with war or, for that matter, with soldering." - Hitler stated in his book Mein Kampf.

Cowboys and Indians gave way to battle re-enactments, especially after the Boer War broke out in Africa. Hitler, now eleven years old, took the side of the Boers against the English and never tired of playing war. Sometimes, he even wore out the boys he was playing with and then simply went and found other boys to continue.

Cowboys and Indians gave way to battle re-enactments, especially after the Boer War broke out in Africa. Hitler, now eleven years old, took the side of the Boers against the English and never tired of playing war. Sometimes, he even wore out the boys he was playing with and then simply went and found other boys to continue.

But now at home, tragedy struck. Adolf's little brother Edmund, age 6, died of measles. Adolf, the boy who loved warplay and its 'pretend' death now had to confront genuine death for the first time. It seems to have shaken him badly.

To make matters worse, the little boy was buried in the cemetery next to their house. From his bedroom window, Adolf could see the cemetery.

Years later, neighbors recalled that young Adolf was sometimes seen at night sitting on the wall of the cemetery gazing up at the stars.

And there were now more problems for Adolf. His grade school years were coming to an end and he had to choose which type of secondary school to attend, classical or technical. By now, young Hitler had dreams of one day becoming an artist. He wanted to go to the classical school. But his father wanted him to follow in his footsteps and become a civil servant and sent him to the technical high school in the city of Linz, in September 1900.

Hitler, the country boy, was lost in the city and its big school. City kids also looked down on country kids who went to the school. He was very lonely and extremely unhappy. He did quite poorly his first year, getting kept back.

He would later claim he wanted to show his father he was unsuited for technical education with its emphasis on mathematics and science and thus should have been allowed to become an artist.

"I thought that once my father saw what little progress I was making at the [technical school] he would let me devote myself to the happiness I dreamed of." - Hitler explained in Mein Kampf.

"I thought that once my father saw what little progress I was making at the [technical school] he would let me devote myself to the happiness I dreamed of." - Hitler explained in Mein Kampf.

There were frequent arguments at home between young Hitler and his father over his career choice. To the traditional minded, authoritarian father, the idea of his son becoming an artist seemed utterly ridiculous.

But in the grand scheme of things, as young Adolf saw it, the idea of a career spent sitting in an office all day long doing the boring paperwork of a civil servant was utterly horrible. The dream of becoming an artist seemed to be the answer to all his present day problems.

But his stubborn father refused to listen. And so a bitter struggle began between father and son.

Hitler began his second year at the high school as the oldest boy in his class since he had been kept back. This gave him the advantage over the other boys. Once again he became a little ringleader and even led the boys in afterschool games of cowboys and Indians, becoming Old Shatterhand. He managed to get better grades in his second year, but still failed mathematics.

Another interest of great importance surfaced at this time, German nationalism.

The area of Austria where Hitler grew up is close to the German border. Many Austrians along the border considered themselves to be German-Austrians. Although they were subjects of the Austrian Hapsburg Monarchy and its multicultural empire, they expressed loyalty to the German Imperial House of Hohenzollern and its Kaiser.

In defiance of the Austrian Monarchy, Adolf Hitler and his young friends liked to use the German greeting, "Heil," and sing the German anthem "Deutschland Uber Alles," instead of the Austrian Imperial anthem.

Hitler's father had worked as an Austrian Imperial customs agent and continually expressed loyalty to the Hapsburg Monarchy, perhaps unknowingly encouraging his rebellious young son to give his loyalty to the German Kaiser.

There was also a history teacher at school, Dr. Leopold Pötsch, who touched Hitler's imagination with exciting tales of the glory of German figures such as Bismark and Frederick The Great. For young Hitler, German Nationalism quickly became an obsession.

Adding to all this, was another new interest, the operas of German composer Richard Wagner. Hitler saw his first opera at age twelve and was immediately captivated by its Germanic music, pagan myths, tales of ancient Kings and Knights and their glorious struggles against hated enemies.

But now, for young Hitler, the struggle with his father was about to come to a sudden end. In January 1903, Hitler's father died suddenly of a lung hemorrhage, leaving his thirteen year old son as head of the Hitler household.

This meant a double dose of supervision, discipline and regimentation under the watchful eyes of teachers at school and his strict father at home. His father, now 58, had spent most of his life working his way up through the civil service ranks. He was used to giving orders and having them obeyed and also expected this from his children. The Hitler family lived on a small farm outside of Linz, Austria. The children had farm chores to perform along with their school work.

Hitler's mother was now preoccupied with caring for her new son, Edmund. In 1896, she gave birth to a girl, Paula. The Hitler household now consisted of Adolf, little brother Edmund, little sister Paula, older half-brother Alois Jr., older half-sister Angela and two parents who were home all the time. It was a crowded, noisy little farm house that seems to have gotten on the nerves on Hitler's father who found retirement after 40 years of work to be difficult.

Hitler's mother was now preoccupied with caring for her new son, Edmund. In 1896, she gave birth to a girl, Paula. The Hitler household now consisted of Adolf, little brother Edmund, little sister Paula, older half-brother Alois Jr., older half-sister Angela and two parents who were home all the time. It was a crowded, noisy little farm house that seems to have gotten on the nerves on Hitler's father who found retirement after 40 years of work to be difficult.The oldest boy, Alois Jr., 13, bore the brunt of his father's discontent, including harsh words and occasional beatings. A year later, at age 14, young Alois had enough of this treatment and ran away from home, never to see his father again. This put young Adolf, age 7, next in line for the same treatment.

Also at this time, the family moved off the farm to the town of Lambach, Austria, halfway between Linz and Salzburg. This was the first of several moves the family would make during the restless retirement of Hitler's father.

For young Adolf, the move to Lambach meant an end to farm chores and more time to play. There was an old Catholic Benedictine monastery in the town. The ancient monastery was decorated with carved stones and woodwork that included several swastikas. Adolf attended school there and saw them every day. They had been put there in the 1800s by the ruling Abbot as a pun or play on words. His name essentially sounded like the German word for swastika, Hakenkreuz.

Young Hitler did well in the monastery school and also took part in the boys' choir. He was said to have had a fine singing voice. Years later Hitler would say the solemn pageantry of the high mass and other Catholic ceremonies was quite intoxicating and left a very deep impression.

As a young boy he idolized the priests and for two years seriously considered becoming a priest himself. He especially admired the Abbot in charge, who ruled his black-robbed monks with supreme authority. At home Hitler sometimes played priest and even included long sermons.

At age nine, he got into schoolboy mischief. He was caught smoking a cigarette by one of the priests, but was forgiven and not punished.

His favorite game to play outside was cowboys and Indians. Tales of the American West were very popular among boys in Austria and Germany. Books by James Fenimore Cooper and especially German writer Karl May were eagerly read and re-enacted.

May, who had never been to America, invented a hero named Old Shatterhand, a white man who always won his battles with Native Americans, defeating his enemies through sheer will power and bravery. Young Hitler read and re-read every one of May's books about Old Shatterhand, totaling more than 70 novels. He continued to read them even as Führer. During the German attack on the Soviet Union he sometimes referred to the Russians as Redskins and ordered his officers to carry May's books about fighting Indians.

In describing his boyhood, Hitler later said of himself that he was an argumentative little ring leader who liked to stay outside and hang around with 'husky' boys. His half-brother Alois later described him as quick to anger and spoiled by his indulgent mother.

In 1898, the Hitler family moved once again, to the village of Leonding, close to Linz. They settled into a small house with a garden located next to a cemetery. This meant another change of schools for Adolf.

He found school easy and got good grades with little effort. He also discovered he had considerable talent for drawing, especially sketching buildings. He had the ability to look at a building, memorize the architectural details, and accurately reproduce it on paper, entirely from memory.

One day, young Hitler went rummaging through his father's book collection and came across several of a military nature, including a picture book on the War of 1870-71 between the Germans and the French. By Hitler's own account, this book became an obsession. He read it over and over, becoming convinced it had been a glorious event.

"It was not long before the great historic struggle had become my greatest spiritual experience. From then on, I became more and more enthusiastic about everything that was in any was connected with war or, for that matter, with soldering." - Hitler stated in his book Mein Kampf.

Cowboys and Indians gave way to battle re-enactments, especially after the Boer War broke out in Africa. Hitler, now eleven years old, took the side of the Boers against the English and never tired of playing war. Sometimes, he even wore out the boys he was playing with and then simply went and found other boys to continue.

Cowboys and Indians gave way to battle re-enactments, especially after the Boer War broke out in Africa. Hitler, now eleven years old, took the side of the Boers against the English and never tired of playing war. Sometimes, he even wore out the boys he was playing with and then simply went and found other boys to continue.But now at home, tragedy struck. Adolf's little brother Edmund, age 6, died of measles. Adolf, the boy who loved warplay and its 'pretend' death now had to confront genuine death for the first time. It seems to have shaken him badly.

To make matters worse, the little boy was buried in the cemetery next to their house. From his bedroom window, Adolf could see the cemetery.

Years later, neighbors recalled that young Adolf was sometimes seen at night sitting on the wall of the cemetery gazing up at the stars.

And there were now more problems for Adolf. His grade school years were coming to an end and he had to choose which type of secondary school to attend, classical or technical. By now, young Hitler had dreams of one day becoming an artist. He wanted to go to the classical school. But his father wanted him to follow in his footsteps and become a civil servant and sent him to the technical high school in the city of Linz, in September 1900.

Hitler, the country boy, was lost in the city and its big school. City kids also looked down on country kids who went to the school. He was very lonely and extremely unhappy. He did quite poorly his first year, getting kept back.

He would later claim he wanted to show his father he was unsuited for technical education with its emphasis on mathematics and science and thus should have been allowed to become an artist.

"I thought that once my father saw what little progress I was making at the [technical school] he would let me devote myself to the happiness I dreamed of." - Hitler explained in Mein Kampf.

"I thought that once my father saw what little progress I was making at the [technical school] he would let me devote myself to the happiness I dreamed of." - Hitler explained in Mein Kampf.There were frequent arguments at home between young Hitler and his father over his career choice. To the traditional minded, authoritarian father, the idea of his son becoming an artist seemed utterly ridiculous.

But in the grand scheme of things, as young Adolf saw it, the idea of a career spent sitting in an office all day long doing the boring paperwork of a civil servant was utterly horrible. The dream of becoming an artist seemed to be the answer to all his present day problems.

But his stubborn father refused to listen. And so a bitter struggle began between father and son.

Hitler began his second year at the high school as the oldest boy in his class since he had been kept back. This gave him the advantage over the other boys. Once again he became a little ringleader and even led the boys in afterschool games of cowboys and Indians, becoming Old Shatterhand. He managed to get better grades in his second year, but still failed mathematics.

Another interest of great importance surfaced at this time, German nationalism.

The area of Austria where Hitler grew up is close to the German border. Many Austrians along the border considered themselves to be German-Austrians. Although they were subjects of the Austrian Hapsburg Monarchy and its multicultural empire, they expressed loyalty to the German Imperial House of Hohenzollern and its Kaiser.

In defiance of the Austrian Monarchy, Adolf Hitler and his young friends liked to use the German greeting, "Heil," and sing the German anthem "Deutschland Uber Alles," instead of the Austrian Imperial anthem.

Hitler's father had worked as an Austrian Imperial customs agent and continually expressed loyalty to the Hapsburg Monarchy, perhaps unknowingly encouraging his rebellious young son to give his loyalty to the German Kaiser.

There was also a history teacher at school, Dr. Leopold Pötsch, who touched Hitler's imagination with exciting tales of the glory of German figures such as Bismark and Frederick The Great. For young Hitler, German Nationalism quickly became an obsession.

Adding to all this, was another new interest, the operas of German composer Richard Wagner. Hitler saw his first opera at age twelve and was immediately captivated by its Germanic music, pagan myths, tales of ancient Kings and Knights and their glorious struggles against hated enemies.

But now, for young Hitler, the struggle with his father was about to come to a sudden end. In January 1903, Hitler's father died suddenly of a lung hemorrhage, leaving his thirteen year old son as head of the Hitler household.

Hitler's Father Dies - January 3, 1903